It’s that time of year again when landscapes in the Mid-Atlantic region are changing beautiful hues of yellow, orange, and red. Outdoor strolls are now accompanied by the crunch of leaves beneath our feet and the crisp autumn breeze on our face. Soon, many of the trees lining our sidewalks and streets will be barren, waiting for the warmer winds of spring to ignite new growth. But wait, some trees don’t lose their leaves in the fall, instead remaining green year-long. Why is this? What is the reason that some trees lose their leaves in the colder months while others don’t?

First, let’s cover some basic terminology. Trees that drop their leaves in the fall are referred to as deciduous trees. In contrast, trees that retain their leaf coverage all year long are referred to as evergreen trees.

Evolutionarily, many evergreen trees and shrubs belong to a group of organisms called gymnosperms, which evolved about 350 million years ago. During this time, nutrients were scarce, and plants often needed to survive long periods of drought. Therefore, many gymnosperms adapted to absorb low levels of light and nutrients all year long. Additionally, to survive these harsh environments, many evergreen gymnosperms have needle and scale-like foliage which possess thick, waxy cuticle layers to preserve water. Popular examples of evergreen gymnosperms at the U. S. Botanic Garden (USBG) include the Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), Nootka cypress (Cupressus nootkatensis), and Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana) trees (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Some examples of evergreen gymnosperms currently on display at the U.S. Botanic Garden.

On the other hand, many deciduous trees and shrubs belong to a group of organisms called angiosperms, which evolved about 140 million years ago. Deciduous angiosperms tend to have thinner leaves with a larger surface area to maximize photosynthetic capacity during the growing season. Adapted to more moderate environments, these plants tend to invest fewer resources toward water conservation and the production of bitter, inhibitory defense compounds; thus, their leaves appear larger and flatter, feel less waxy to the touch, and are much tastier to herbivores and plant pathogens compared to their evergreen counterparts.

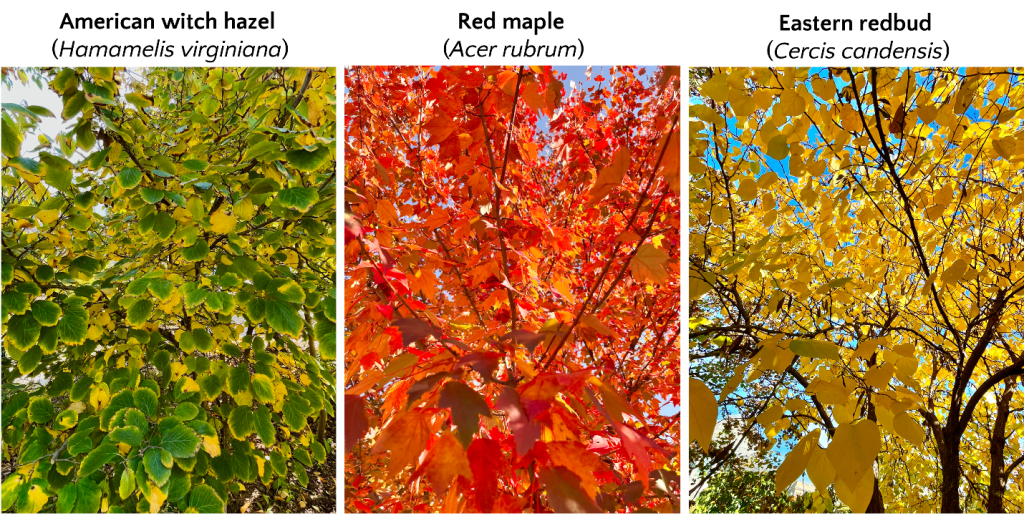

While deciduous plants are photosynthetically productive during the warmer months, their leaves are not built to withstand winter. Therefore, as temperatures and light intensity decrease during the fall, deciduous plants prepare for dormancy by decreasing their production of chlorophyll and beginning to re-absorb essential nutrients contained within their leaves. Chlorophyll is a compound in plant leaves which is essential for conducting photosynthesis, and it gives plant tissues their green color. As chlorophyll concentrations diminish within the leaves of deciduous plants, the colors of the remaining compounds become more prominent.

Some common pigmented compound classes include carotenoids (yellow and orange hues), anthocyanins (red and purple hues), and tannins (brown hues). Some deciduous angiosperms at the USBG which display vibrant leaves in the fall are American witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), red maple (Acer rubrum), and Eastern redbud (Cercis candensis) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Examples of deciduous angiosperm trees currently on display at the U.S. Botanic Garden’s Bartholdi Gardens.

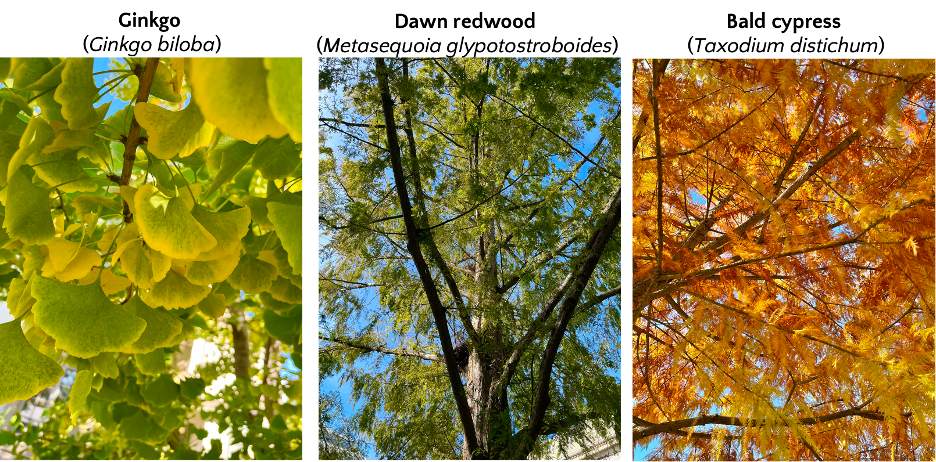

While it would be easy to say that all gymnosperms are evergreen and all angiosperms are deciduous, as with many things in biology, there are always exceptions to the rule. For example, there are several gymnosperms which are deciduous, including the USBG’s ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), dawn redwood (Metasequoia glypotostroboides) and bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) (Fig. 3). There are also angiosperm trees and shrubs which are evergreen, including the Garden’s American holly (Ilex opaca), Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), and variegated boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Examples of deciduous gymnosperm trees currently on display at the U. S. Botanic Garden’s terrace garden.

Figure 4: Examples of evergreen angiosperm trees and shrubs currently on display at the U. S. Botanic Garden’s Regional Garden.

The example trees and shrubs shown are just a few of the beautiful plants currently on display this fall in the outdoor gardens. Be sure to stop by to see our stunning deciduous plants before all of the leaves drop! Then return enjoy the evergreens during the winter months.

Want to learn more about deciduous and evergreen trees and the adaptations made to survive harsh conditions? Look for the USBG’s on-site ‘Conifer Discovery Cart’ during an autumn or winter visit or look through the reference materials linked below.

Reference materials and additional educational resources:

Videos:

Nature Clearly. (2023). Why do leaves change color and get shed before winter? | Leaf cycle of deciduous trees. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Z64EQa6MjE.

Next Generation Science. (2023). Gymnosperms. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fg31Wym998E.

PBA Eons. (2021). When Trees Took Over the World. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrwMUQbUR30&t=1s.

Texts:

Brunning, A. (2014). The Chemicals Behind the Colours of Autumn Leaves. Retrieved from: https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/09/11/autumnleaves/.

Givnish, T. J. (2002). Adaptive significance of evergreen vs. deciduous leaves: solving the triple paradox. Silva Fennica. 36(3): 703-743.

USDA Forest Service. (nd). Science of Fall Colors. Retrieved from: https://www.fs.usda.gov/visit/fall-colors/science-of-fall-colors.

[IE1](corrected capitalization in American witch hazel)